funding from the art up

Susan Jones wrote a powerful piece for Rewild a couple of weeks ago. It set me thinking.

Susan described a “slow-moving, self-interested hierarchy of regularly-funded institutions” moving straight to the front of the queue for government’s Covid-19 emergency support (quick when they

need to be, then); while the great majority of actual artists had been left to fend for themselves.

This institutional model was devised by the original Arts Council of Great Britain in 1946, with the best of intentions. Back then (as now) the Arts Council preferred to fund not-for-profit

organisations with boards of trustees formally responsible for the proper use of funds handed out. To keep costs to the taxpayer down, the Arts Council encouraged funded organisations to raise as

much money as they could from other sources – again a sensible strategy for good times.

Marketing, development and education/outreach departments expanded in order to maximise the total income available to funded organisations. They aimed to pull in all available grant income, build

relationships with donors and sponsors of every stripe, and for ticketed events sell as many as possible for as much as possible.

In good times, the combined efforts of arts managers and development and marketing professionals generated more than enough income to cover their salaries, and the money left over paid for art.

Artists (typically freelance) were hired to produce the art. All looked well. Arts Council grants went into the system and plenty of art came out.

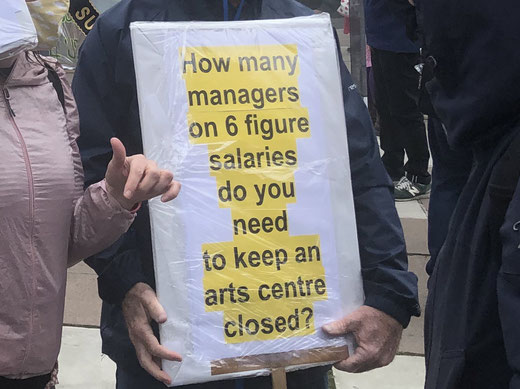

Covid-19, as artists have found to their cost, stopped the art coming art and dammed the income streams that only flow when art is coming out. The system (we can see now) generated art as a

by-product of wider managerial operations. The system could, if government wanted it to and kept emergency funding flowing, continue to exist for months or years without producing any art at

all.

As policymakers prepare to support resurgent art when the crisis is over, they need to do that as far as possible in partnership with artists themselves. New rules of engagement with funded

organisations would be helpful too, designed to keep management expenditure down to a functional minimum and so push as much money as possible out to artists making actual art. Funding from the

art up, we could say, in place of “trickle-down” funding to art through ever-thickening layers of managerial sediment. Susan Jones called it trickle-down funding, and she called it right.

Andrew Pinnock 2020